By Scott T. Clein, P.E., LEED AP

Reposted with permission from the Michigan Municipal League’s May/June issue of The Review magazine

Pedestrian-friendly … walkable … You’ve most likely heard, and used, these terms when describing the future vision of your community. You’ve also likely heard about Complete Streets and assumed it was the same thing.

Technically you’re right…and wrong. While Complete Streets initiatives do improve the walkability of roadways, the concept includes so much more. Before your community takes a dive into the Complete Streets waters, you need to understand whether or not you’ll need a life vest.

In 2010, Michigan joined a growing list of states that enacted legislation related to Complete Streets. Two bills passed that added the phrase to the legislative vernacular and requires the Michigan Department of Transportation to create a Complete Streets policy that serves as a model for communities.

But what is the concept really all about? Below are common definitions that should be considered during Complete Streets planning and discussions.

COMPLETE STREETS is a movement that designs and operates roadway corridors promoting safe access for all users. Roadways, therefore, should accommodate vehicles, transit, bicyclists, and pedestrians of all ages and abilities.

UNIVERSAL ACCESSIBILITY emerged as an offshoot of barrier-free design. It’s the idea that good design must take into account the age and ability of all users from the beginning, even if it means exceeding minimum standards to allow for a better use of space.

GREEN STREETS encourages sustainability in the design and construction of roadways by using the latest best management practices, such as rain gardens for improving stormwater quality.

GREEN STREETS encourages sustainability in the design and construction of roadways by using the latest best management practices, such as rain gardens for improving stormwater quality.

LIVING STREETS states pedestrians must be properly included in transportation designs. It goes beyond simply adding sidewalks to include active use of the corridor, such as outdoor dining and sales, and neighborhood festivals.

With a clearer understanding of Complete Streets improvements, here are five common myths that may get in the way of planning and implementation.

Myth 1: It’s expensive.

Designs in line with Complete Streets philosophies don’t have to cost a lot, especially when included in annual capital improvement projects. Most communities have existing funding for road maintenance and related upgrades. When resurfacing a roadway, for example, implement bike lanes for little to no added cost.

This piece-by-piece approach may seem out of place when attempting to promote connectivity, but it mimics road maintenance approaches and allows the largest benefits from shrinking budgets.

Myth 2: On-street bike lanes are unsafe.

On the contrary, studies show that on-street bike lanes, when properly marked and signed, are safer for bicyclists and pedestrians than sidewalks.

The Transportation Research Board published a study by William Moritz at the University of Washington referencing the Relative Danger Index, which measures bicycle-accident frequency to distance traveled. A higher number represents a greater danger. Sidewalks have an RDI of 5.30 while streets with dedicated bike lanes have an RDI of 0.50.

The Transportation Research Board published a study by William Moritz at the University of Washington referencing the Relative Danger Index, which measures bicycle-accident frequency to distance traveled. A higher number represents a greater danger. Sidewalks have an RDI of 5.30 while streets with dedicated bike lanes have an RDI of 0.50.

Clearly, it’s a misperception that bicyclists are at greater risk on roadway bike lanes. This on-street myth is also perpetuated by the notions that drivers won’t change their driving habits in the presence of a bicyclist and that roadways are only built for vehicles.

Myth 3: It’s only for urban communities.

Urban areas will undoubtedly benefit the most from Complete Streets improvements because of dense pedestrian activity. However, let’s imagine a rural suburban community that has, during the last 30 years, shifted from primarily agricultural land uses to single-family residential developments.

Typically, these developments are islands surrounded by farmland with intermittent access to an open-shoulder country road. They are not truly connected with other neighborhoods and do not allow residents to safely walk or bicycle outside of their subdivision.

Now imagine the same two-lane country road with a paved bike lane along the shoulder. Then add a large shared-use pathway beside the right-of-way line for pedestrians and less-accomplished bicyclists. The result is safely linked subdivisions and a community that is making a dynamic statement about its values.

Myth 4: It negatively impacts traffic flow.

Well…yes, it might. Accommodations for pedestrians and bicyclists may increase driver delay or reduce vehicle speeds. But this is not always a bad thing.

Pedestrian spaces and dedicated bike lanes can create an inviting atmosphere. In addition to promoting a healthier lifestyle, this can help foster the spirit that cool communities seem to have. This so-called “it” factor entices people to live in a neighborhood or city center and directly translates into positive community economic development and financial sustainability.

While there can be repercussions, such as altered traffic patterns that negatively impact surrounding streets, transportation engineers must look at their network holistically and reconsider pavement geometry to encourage safe driving.

Myth 5: “We ARE a walkable community, so this won’t change our plans.”

Some communities have embraced the Complete Streets concept. Still, disagreements between planning and engineering staffs continue largely because of these myths. Simply being walkable does not make a Complete Street. What about ADA compliance and other street amenities? Significant opportunities spring from combining the power of the planning, engineering, and economic development areas of local government.

Consider an engineering department that actively promotes the construction of smaller roadways to incorporate bike lanes, wide sidewalks, and universal design principles. What if the planning department aligns these improvements with zoning ordinances to encourage mixed-use developments with outdoor dining and pedestrian-scale amenities? Now, the economic development director has added firepower to actively recruit businesses and developments. Uniting these groups can unleash the powerful potential to positively impact a community.

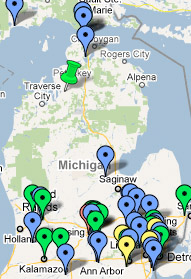

This last point is the overarching benefit that must be understood about Complete Streets. When properly infused into a community, a Complete Streets mentality can help unite economic development, land planning, and transportation engineering for bettering the overall quality of life. All community leaders would benefit from understanding the definitions and implications, but also keeping in mind the myths discussed. With the proper perspective and conviction, Complete Streets can make every Michigan community a better place to live.

Giffels-Webster

Giffels-Webster Engineers, Inc. is a civil engineering, surveying, planning, and landscape architecture firm with a 55-year history of serving municipalities and governmental agencies throughout Michigan.

For more on Giffels-Webster, visit www.giffelswebster.com

Scott T. Clein, P.E., LEED AP is an associate at Giffels-Webster.

You may reach him at 313-962-4442 or [email protected].

Leave a comment

Comments feed for this article